Susan Ostrowski, MA, MS, CCC-SLP

Susan Ostrowski, MA, MS, CCC-SLP

Reading2Connect, Co-Founder

Mr. D stared out the window. When I approached him, he asked, “Tomorrow’s Sunday?” I said “Yes.” He looked forlorn.

For years, Mr. D and his family had discussed the week’s political events over Sunday dinner. But as Mr. D’s dementia progressed, Sunday dinners were becoming disheartening for everyone. He could no longer read his favorite political journal. “Of everything going on,” he said, “reading is what I miss most. I can’t read anymore.”

It was at this moment that I first questioned an unspoken assumption. Does dementia really strip individuals of their capacity to read an article or short story? What is the relationship between dementia and reading?

For many older adults, the capacity to read is like a pearl. It’s buried in the clutter of vision deficits, attention difficulties, and the dreaded short-term memory problem. Because of these impairments which are related to reading, people with dementia have great difficulty reading conventional books, magazines, and newspapers.

But this does not mean they cannot read.

When people in long-term care are presented with reading material adapted for them, the automatic, deeply-rooted skill of reading resurfaces. With print adaptations that compensate for cognitive changes, text becomes accessible. While some of these text modifications are simple and easy to implement, others require a deeper understanding of the barriers to reading.

When people in long-term care are presented with reading material adapted for them, the automatic, deeply-rooted skill of reading resurfaces. With print adaptations that compensate for cognitive changes, text becomes accessible. While some of these text modifications are simple and easy to implement, others require a deeper understanding of the barriers to reading.

If you would like to try your hand at creating “dementia-friendly” reading material for an elder in your life, take a look at the list below. We’ve outlined the preliminary steps to make text more readable for older adults. Keep in mind that every person’s cognitive profile is unique. The format that works for one individual may not work for another. However, these steps will start the personalized, collaborative, ongoing process that is needed to unlock the gift of reading for adults living with memory challenges.

1) Document

Copy an online short article or story into a document.

2) Font

Change the font to non-serif, bold, and large. 20pt size is a good place to start. These changes help with visual acuity, visual contrast, and visual tracking.

3) Language

To ease the working memory burden and to make language processing less effortful, change the long, complex sentences to short, direct sentences. At the same time, make sure the writing is good writing; it has to flow smoothly for ease of reading. If you can achieve a gentle, lyrical rhythm to your piece, all the better.

4) Main Idea

Delete tangential, excessive details. Selective attention difficulties make it hard for some elders to hold onto the main idea when it is embedded in too much information.

5) Images

Insert clear, colorful, easy-to-recognize pictures throughout the document. Images are critical for multiple reasons.

Abundant color pictures capture the reader’s attention and make the text less intimidating and more inviting. Images that are directly related to the text help readers remember what they read on previous pages. In addition, illustrations give the reader a place to rest, to take breaks from reading, without losing the topic. Abundant pictures also allow elders to interact with the book by themselves, or with peers, without needing care partner assistance. Perhaps most importantly, images encourage conversation and bring a social component to the reading experience.

6) Content

Of all the features that make reading dementia-friendly, the most essential is quality content. For many elders, reading takes work. Therefore, it has to be worth their effort. The content has to be compelling, amusing, pleasing, or thought-provoking. There has to be energy throughout the piece to keep them going.

Of all the features that make reading dementia-friendly, the most essential is quality content. For many elders, reading takes work. Therefore, it has to be worth their effort. The content has to be compelling, amusing, pleasing, or thought-provoking. There has to be energy throughout the piece to keep them going.

Also, there needs to be the right balance of familiar and novel content. Our readers say consistently that, when they read, they want to learn something. If it is dry, dull, obvious, or foolish, they will put it aside.

I remember the first time I offered an adapted booklet to a woman living with dementia. I did not tell her that I created the booklet. Feeling quite proud of myself, I sat quietly while she worked through it. When she was done, she said with a kind smile, “Thank you, dear. It wasn’t worth a whole lot, but thank you.” When I read the booklet again, this time through her eyes, the word that came to mind was insipid.

Older adults with memory challenges remember what it’s like to read. They expect the same quality reading experience now as they enjoyed in the past.

Older adults with memory challenges remember what it’s like to read. They expect the same quality reading experience now as they enjoyed in the past.

And therein lies the fun challenge before us: to create reading material that is carefully formatted and highly-readable while retaining the integrity of adult literature.

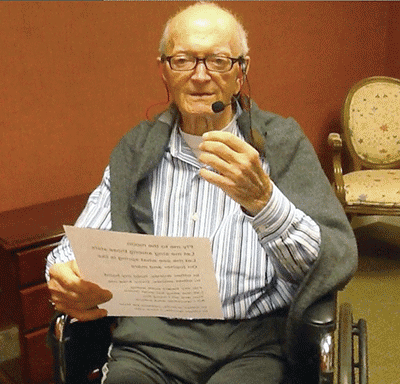

In Mr. D’s case, we worked intensely for three weeks analyzing the breakdowns in the reading process for him. Experimenting with different elements, we found a print format that enabled him to read again. The text tapped into his life experience and wisdom. Mr. D was able to read and comment with relevance and originality. The first time it all clicked, he said with a trembling voice, “I feel saved.”

Developing good quality, comprehensible reading material for our elder citizens takes time and work. But losing access to culture, literature, and information should not be a part of aging. Accessible reading is everyone’s right.