Promising Practices in Dining

Innovative examples of how providers are changing their dining practices so that it is a more dignified, pleasurable experience

Examining the Institutional Dining Experience: From Traditional Dining to Person-Directed Dining

While each nursing home possesses a unique culture and set of dining-related issues, the common nursing home dining experience seems to be intricately tied to the structure of systems that typically accommodate multiple dietary regulations and operational efficiencies. Nursing homes have established multi-disciplinary systems which intersect with a complex dining process. Over time the nursing home dining experience has become institutionalized, and in many instances dining is not a pleasurable experience for residents. The CMS Interpretive Guidelines reinforce the need for nursing homes to re-evaluate resident quality of life, including the methods by which providers honor resident dignity and choice in dining.

Choice Matters

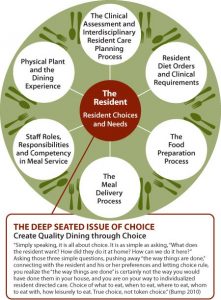

The Resident is always at the core of multiple processes that affect the resident.

Before a resident meal can even be served, a clinical team (interdisciplinary care plan team) must properly assess each resident for food and dietary related risks, preferences, and then identify and order the correct diet. A number of indirect and direct care givers may provide input into this resident care planning process including but not limited to: the resident him/her self, the resident’s legal decision-maker, and a host of team members such as a registered dietician, physician, speech-language pathologist, occupational or physical therapist, nursing assistant and dietary aide. At the center of this care planning process is the goal of correctly assessing the resident’s clinical needs and food preferences upon admission and throughout his/her stay in the nursing home.

Before a resident meal can even be served, a clinical team (interdisciplinary care plan team) must properly assess each resident for food and dietary related risks, preferences, and then identify and order the correct diet. A number of indirect and direct care givers may provide input into this resident care planning process including but not limited to: the resident him/her self, the resident’s legal decision-maker, and a host of team members such as a registered dietician, physician, speech-language pathologist, occupational or physical therapist, nursing assistant and dietary aide. At the center of this care planning process is the goal of correctly assessing the resident’s clinical needs and food preferences upon admission and throughout his/her stay in the nursing home.

The following is an excerpt from Linda Bump’s, “The Deep Seated Issue of Choice” from the 2010 Creating Home in the Nursing Home II: A National Online Symposium on Culture Change and the Food and Dining Requirements. It reflects how the institutional dining process does not maximize a resident’s ability to have control over the dining experience.

“Traditionally we define choice in our dining services as the opportunity to express our likes and dislikes during an admission interview, or to circle a menu one day, or week, or month in advance. We may also define choice by the presence of the steam table in the dining room, but it quickly becomes token choice with the use of computerized tray ticket systems which control the food served from the steam table to a specific resident. What could be worse than seeing and smelling a tempting food, only to be served a different food specified on the ticket laying on the pre-set table – resident autonomy at this particular meal is overridden with preferences stated during an assessment process or a therapeutic diet extension. And sadly, acknowledge to yourself how often the dining and nursing staff expresses their frustration with impossible-to-please residents who select something they have previously asked us not to serve them. Consider the control you personally exercise daily in dining choices, and the pleasure that control brings to you each day with food.” (Bump 2010)

Maintaining Dignity Throughout the Dining Process: Going from Traditional Methods to Person-Directed Dining Methods

Food Preparation

Traditional: It is typically the dietary department’s responsibility to receive resident diet orders and then create diet cards, diet indexes, meal tickets and/or enter new information into a host of computer and/or paper-based resident diet recognition systems, which are directly linked to meal preparation and eventually to food ordering and inventory management. In a central kitchen, where most meals are traditionally prepared, the dietary staff must comply with a host of regulations.

Traditionally, a cook may prepare several entrees and alternatives in accordance with a planned menu and any therapeutic diets that must be served. As food is prepared, it is typically maintained in a steam table where the plating of food on resident meal trays begins. At this point, the meals are “transported” to various locations where residents will be served. Some nursing homes even use an overhead paging system to announce “Trays are up!” just to make sure that designated staff rush from ever corner of the nursing home to assist with the dining process.

Person-Directed Dining: Maintaining dignity in the food preparation process would incorporate all of the residents dietary requirements, but ensure that the food is prepared based on the dietary preferences of the person, as well as presenting food in an appealing way. This would include not presenting food which is pureed or cut into small pieces in piles on a plate, or blended food in a way that does not take into consideration how the blended foods taste. In some places, trays are not used and meals are delivered to each person while sitting at a dining table with other residents, in more of a restaurant style setting. The type and color of plates is often considered too in food preparation in order to help with the person’s ability to see their food and enjoy eating it. Each care community will need to decide what preparation changes will work for them to provide a more person-directed experience that maintains dignity and joy in the dining process.

Meal Delivery

Traditional: Once meals carts and trucks are delivered to the various resident dining locations, nursing care givers are usually assigned to serve the meals to each resident. Since most meal trays are typically organized by resident room or wing or by residents who eat in a particular location, nursing staff can quickly remove meal trays from tray trucks and serve them to residents efficiently. Typically, at all meals, staff scramble to ensure residents are “ready” for meals. This may include the practice of awakening residents who are sleeping, interrupting resident activities, or otherwise imposing a rigid dining schedule. Residents are “transported” to and from various locations in order to eat. In some instances, residents may choose to remain in their rooms to eat meals and in others they may be required to eat in a particular location.

Person-Directed Dining: Trays are not used and meals are delivered to each person while sitting at a dining table with other residents, in more of a restaurant style setting. Residents may not all need to eat at the same time and residents’ desires for eating times may be taken into consideration. Getting a person “ready” for a meal is be done slowly and with engagement rather than rushing to get the person up. Some care communities may be able to allow their residents to remain sleeping and let them eat later, when they are ready. Each care community is different, but care can be taken into how residents are prepared for meals and how the meals are delivered.

The Dining Experience

Traditional: Many residents find the dining experience to be undignified, sterile, and part of a daily task that must be accomplished. Residents who require assistance with meals are often provided with assistance based upon the resident’s need and both the ability and availability of a trained staff member to assist them. Some require only partial assistance such as ensuring that the resident’s meal is within reach of the resident and that all the resident’s needed utensils are present. In other cases a resident may require complete assistance with pre-meal and post-meal grooming and the entire process of eating. In an institutional setting, staff members are assigned to residents to ensure adequate meal supervision and assistance. Often staff refer to these residents as “feeders,” and in an institutional setting staff may even maintain “feeder” lists, an institutional label that CMS has identified in its release of Interpretive Guidance changes F-241 (Dignity)

The “clothing protector” (thought to be a more adult, dignified term than “bib”) experience also has institutional roots as it was originally designed to protect and promote resident dignity. Many providers simply routinely apply a clothing protector to each resident at all meals. It has been a method used to preserve a resident’s appearance and dignity by preventing food spills on his/her clothing. Regardless of the name, the use of a clothing protector (aka “bib”) has also been identified in the CMS Guidance as an undignified practice in the release of the Interpretive Guidance F – 241 Dignity.

Person-Directed Dining: Care is taken when assisting a person in eating. Special utensils may be provided for persons with hand tremors or other manual dexterity needs. Those who are typically referred to as “feeders” are fed in a dignified way, with the care partner engaging the person as if they are actually at a meal together and the person is not rushed through the eating process. “Clothing protectors” may not be needed depending on how the person eats and the care partner assists with feeding the person in a way that minimizes spills and stains. When clothing protectors are used, they are made to be an attractive addition to the person’s clothing and not look like a “bib” that a baby would wear. Again, each care community will need to assist with eating in their own way which fits with their organization, but dignity and personal needs and wants are always considered in person-directed dining.

Person-Directed Dining: Trays are not used and meals are delivered to each person while sitting at a dining table with other residents, in more of a restaurant style setting. Residents may not all need to eat at the same time and residents’ desires for eating times may be taken into consideration. Getting a person “ready” for a meal is be done slowly and with engagement rather than rushing to get the person up. Some care communities may be able to allow their residents to remain sleeping and let them eat later, when they are ready. Each care community is different, but care can be taken into how residents are prepared for meals and how the meals are delivered.